Strange Fruit (2024)

Image of the Relf sisters from 1973 Ebony Magazine In a 1973 Ebony magazine edition, the Relf sisters struck their poses. The sepia-toned photograph conjures an air of distance, as if this image had been taken in some long-ago era. Minnie Lee, the older of the two sisters, looks deep into the camera. Her gaze is unwavering and direct, deadpan yet simultaneously pleasant. She is dressed in what one may call her “Sunday’s best”: a clean, freshly pressed white dress. Her right hand clasps what seems to be a white glove, typically worn by church ushers, and her left is draped around her younger sister, Mary Alice, who is two years younger at 12 years of age. Unlike her sister’s stalwart gaze, Mary Alice dons a large, lively smile, her hair is braided neatly. She sports a patterned lavender-colored dress, the bottom of which contorts as she rests her right arm, which is not fully developed because of a genetic disability, on her sister’s shoulder.

Earlier that summer, Minnie Lee and Mary Alice were taken from their home in rural Montgomery and involuntarily sterilized without the informed consent of their parents by a federally funded clinic. This atrocity was able to occur because of the almost unanimous ruling of the 1927 Buck v. Bell Supreme Court case. Speaking for all but one justice, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes revitalized the otherwise fading public eugenics movement in just 40 words by saying:

“It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.”

Put plainly, some lives are more important than others. The sisters were stripped of their ability to procreate because they – Black girls, of an impoverished, uneducated ilk – were deemed intellectually and socially inferior. Despite abiding by the norms of Western femininity in their dress, they were looked upon as less than, considered unfit to bear children and unworthy of motherhood. The details of Carrie Buck’s and the Relf sisters’ cases are rooted in the longstanding American paradox of who belongs – who is entitled to citizenship and thus basic human rights. The lines here are blurred, however, because one can no longer sum the brutalities of this “othering” to racial difference. Buck was an impoverished young white woman, and the Relf sisters were Black. The reason these individuals were subject to sterilization was because they identically deviated from what scholar Rosemarie Garland Thomson terms the “normate”: white, heterosexual, male, able-bodied. They represented communities whose narratives ran antithetical to the fabric of American foundings. From the research done, I cannot state how Carrie Buck represented herself in her trial, but the Relf sisters, dressed in unmistakable garb of womanhood – their white and purple dresses – were still deemed eccentric to what it meant to be ladylike. Buck and the Relf sisters’ stories highlight the jarring reality that for people who are seen as different, their social worth lies not in their contributions, but in their erasure.

Untitled (2024)

Deborah Roberts Subject America #3, 2021. Mixed media collage on canvas In front of a white backdrop a young Black girl boldly strikes a pose. Her Brahmatic facial structure is composed of four distinctly different visages. Her left jaw line and ear come from a different person than her left eye and forehead, which have different origins than her right eye and smile, and are altogether separate from a face that juts out of the right side of her head, looking off into the distance. Above this conglomerate sit five tightly coiled bantu knots wrapped in a red and green scarf (two of the three colors of the pan-African flag). She sports a peach swimsuit with a large red, white and blue insignia across the front that reads “American” upside down, as if to say that such apparel is a knock-off or counterfeit – as if to suggest that the wearer is similarly a fraud.

This little girl represents the intricate and nuanced reality of Black childhood. Her story did not begin with herself, but rather her ancestors – those that came before her; the face that looks off into the distance reminding her of her past and informing her present. She is rooted in their traditions. From the crown of her intricately braided hair, to the soles of her richly pigmented feet, she is a sum of many generational parts. Her complex history – her very being – is one that is endemic to her contingent of the African diaspora.

The question then becomes, what happens if her story, like the stories of many other Black children – the stories that undergird the history of American democracy – are never told? What is lost in spheres of primary education and learning if her voice(s), her perspective(s) is not shared?

These were the questions that sparked the hearing of five Supreme Court cases that are collectively known as Brown vs. Board of Education. The central argument of this case was that separate school systems for Black students and white students were inherently unequal, and a violation of the "Equal Protection Clause" of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In other words, Black students were not “separate but equal”. They were disenfranchised by a segregated schooling system and were not afforded the same, necessary privileges to succeed scholastically.

Scholar and (then) attorney Thurgood Marshall presented the results of sociological tests, such as the one performed by social scientists Kenneth and Mamie Clark, arguing that segregated school systems resulted in Black children internalizing an unnamed inferiority. This “double consciousness” as DuBois terms it, is the same phenomenon captured by photographer Gordon Parks in his image Doll Test.

Subject America #3 is such a potent comment on the Brown v. Board case – though painted almost seven decades later –because it begs a question that has been historically disregarded and shied away from: what is afforded to white American children through the integration of primary education settings? How can the experiences of a young Black student enrich the lives – and futures – of young white students? How does such integration work to proactively elicit ideals of representational justice and impact the psychological phenomenon Douglass terms the “internal picture gallery”? The answers to these questions aren’t as elusive as they may seem. It is through the acceptance and understanding of our neighbors’ uniqueness that we become closer to realizing the true potential of the American experience.

The Women are Here (2023)

Chuck Stewart, lady wearing book hat, c. 1960. Silver gelatin print mounted on boardThis work, lady wearing book hat (c. 1960) by Chuck Stewart, is a piece displayed in the exhibit I curated for the Cleveland Orchestra, The Magic Lens: A Photographic Journey by Chuck Stewart. It is representative of the exhibition tenet: power of presence. Works in this category depict those who made space at tables that were never meant to seat them, forcefully claiming each “unalienable right” and realizing the previously unthinkable potential of American democracy by simply existing. Here, a woman – a Black woman– dons a hat made of a book containing a statuette and newspaper article whose title reads, “The Women Are Here”. She is declaring her presence in an era where she is doubly miscounted by systems of both racial and gender oppression. Her existence is contextualized by what scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw defines as intersectionality. And yet, she smiles. In this moment, she claims joy and ebullience over of negativity.

Gil (2023)

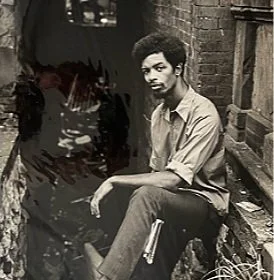

Chuck Stewart, Gil Scott-Heron, July 1970. Silver gelatin. Harlem NYC

This piece, Gil Scott-Heron (1970) by Chuck Stewart, was also a part of the Magic Lens exhibit and was a representation of the exhibition tenant: power of rhythm. There is a natural rhythm about this work. The first and easiest understanding of this idea is in the depiction of Gil Scott-Heron, one of America’s greatest jazz musicians and poets. The very idea of poetry implies meter and rhythm; there’s a cadence to which such work is written and spoken that distinguishes it from other literary art forms. Scott-Heron, one year after this photo was taken, released one of his most famous albums, Pieces of a Man, on which the song entitled, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” was recorded. This work was a declaration of progress by any means necessary. He suggests that change will not be given by large and powerful corporations, but rather must be taken by those that require it. Scott-Heron’s steady gaze and posture here is almost a foreshadowing of this ideology. He sits as if he is at the threshold of action, poised and positioned to realize his message at any moment.